SUNDAY

I began my week of “Reimagining Human Relations in our Time” not Tuesday at the Tavistock Institute, but Sunday at the Tate Modern. What I saw there—and the themes it brought to mine —shaped the powerful reimagining I did over the course of the week.

In a week full of experiences and panels that would deeply affect me, the one that got it all off to an amazing start wasn’t at the Tavistock Institute at all. I’d arrived in London from Philadelphia early Sunday morning, managed to get into my room, take a jet-lagged nap, and then head to the Tate Modern, where their experimental Exchange space was hosting Art:Work (found here.)

Art:Work explores the power and politics of making in the age of digital labour. Drop in and take part in a creative interdisciplinary lab where artists, technologists, designers and musicians question how and by whom (or what), art and ideas are being generated in the digital age.

That afternoon, they were holding a panel discussion that sounded like an amazing way to start a week. Indeed, the focus on encounter between modern and postmodern labor, traditional and new conceptions of art, value and humanity would suffuse the entire Festival. In my mind, a Tavistock Institute whose origins were in the socio-technical research of work and human relationships would meet a Tate that was witnessing art emerge into new media, new economies and new technologies.

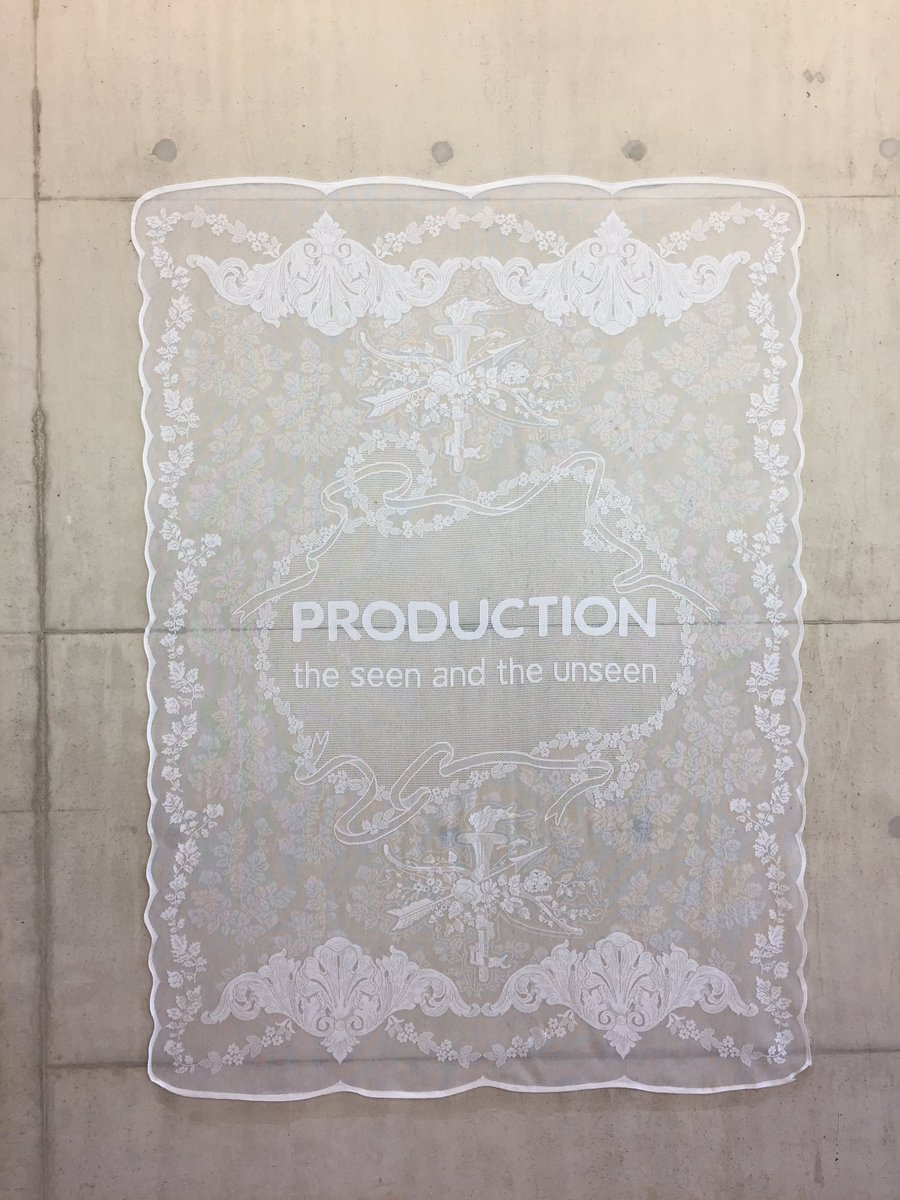

If the 70th Anniversary Festival was going to take me back to World War Two officer selection, deep into coal mines, on board ships, and in factories—places rooted in mid-20th century industrial landscape—then this would be a fascinating parallel investigation into the changing world of Art:Work. In a fascinating turn, the exhibit began with some confrontationally old-fashioned artifacts of labor. We punched a time card when we entered the exhibit space, and we were greeted by a woven lace tapestry that looked like it could have been the finest Nottingham craftsmanship, were it not for the words “Production: the seen and the unseen” woven in its center.

This set the tone for an exhibit—really part maker-space, part craft workshop, part meeting-space, and part traditional exhibit—where ideas of work, craft, art, value, compensation, ownership, and agency were all put into question, set against the encounter between analogue and digital technologies and artistic techniques.

The panel itself began with a moving presentation about e-NABLE, a crowd-sourcing operation to 3D printed prosthetic hands for children all over the world.

This was followed by a presentation by an engineer from RedHat, the software company behind Linux, the open-source operating system. He offered a compelling picture of the power of openness, collaboration, crowd-sourcing and the community dynamics that lead make crowd-sourcing something as complex as an operating system possible.

Things didn’t stay so upbeat, though. Quickly, the panel took up the issues of privacy, ownership, surveillance, and control that sharing, crowd-sourcing, and openness raise. Rachel Rayns offered a portrait of her high-tech, off-the-grid “van life” (living out of a customized caravan, complete with solar panels, smart home technologies, and full of her crafting projects). She focused on her attempts to disintermediate her connectedness, so that the connections between her local internet-of-things (IoT) aren’t mediated by servers owned by one internet giant or another. She offered a charmingly simple vision for an internet-of-things untethered to the mega-market dynamics of the internet, defining her IoT as

“little computers talking with each other.”

An Internet of Things of her own.

Irini Papadimitriou brought her background in museum studies to the collaboration between the Mozilla Foundation and the Victoria and Albert Museum. She described how they were working together to facilitate (and preserve, curate and display) open creativity and creative problem solving. Her suggestion that artists have a role in creatively engaging the challenges of the era —and the inclusion of artists in this year’s MozFest (Digital Design Weekend)—would be echoed later in the week by the Tavistock itself having an artist-in-residence participate in its institutional a life and problem solving.

Finally, I found Ramon Amaro to be the most provocative and engaging speaker of the day. His presentation is worth quoting at some length:

As machines learn to perform more complex tasks, questions begin to arise about what role machines will play in future decisions and decision making… Despite the recognized benefits of AI in automation, on productivity and reduced human toil, issues arise over how the accelerated growth of machine capabilities and automated work environments may result in increased job loss and the so-called hollowing out of what me know as work today. Some estimate that 60% of the work currently being performed [by humans] will be entirely replaced by machines.

Amaro’s talk set the stage for a week of socio-technical analysis of labor. Whereas the Tavistock would focus on the human processes in among the machines, Amaro examined the way machine processes could determine the possibilities of our humanity. In a fascinating turn, he found in the early days of photography an antecedent of the interaction between human and machine in our contemporary era. Specifically, he saw the ability of photography to record and quantify human movement (i.e., to turn motion into points of data) as the technology that enabled Fordism, and linked it to the contemporary algorithmic processing of the entirety of human behavior, now recorded in digital data. In this way, he brought into stark relief the way that a machine’s capacity to rationalize human labor could enable unforeseen efficiencies and scale the benefits of technology like never before, or lead us down a path of ever accelerating dehumanization.

He concluded, however, with a much-needed caution against projecting our agency onto the algorithm:

What I want to challenge is the common misperception that the algorithm itself is racist, the algorithm itself is homophobic or queer-phobic, or… But really seeing the algorithm itself as a new expression of the existing social inequalities that we ourselves are articulating… People often ask me, “At what point will the algorithm kill us?” And the question itself is distracting because we see now, especially in the political space…that we will kill ourselves well before the algorithm.